The Evidence-Based Contest Prep Guide: HOW to train and WHY

Competing in bodybuilding involves restricting your calorie intake and increasing your energy expenditure to lose as much bodyfat as possible. Simultaneously, you’ll be doing hypertrophy training to minimize muscle mass loss or even gain some. The high amounts of NEAT coupled with a low bodyfat level and a chronic energy deficit means your training will likely need to be different from what you would usually do. The biggest issue you’ll encounter is an increased injury risk. To minimize this risk, shifting towards more machine-based, higher repetition and slower tempo work is likely beneficial. Read on to find out how to train during the different phases of a bodybuilding contest preparation diet!

This post will be the first in a series of posts on how to prepare for a bodybuilding contest. Other topics covered will most likely include nutrition, supplementation, peaking strategies and posing. The information provided will partly come from large amounts of anecdotes and partly from the literature. While anecdotes suffer from many limitations that various research designs do not, the evidence on bodybuilding specifically is (understandably) pretty sparse. Because of how sparse the bodybuilding literature is, I’ll also draw some studies from the relative energy deficiency literature - more on that later.

What happens to training when we prep?

Before we can address potential training issues that occur during prep, we need to understand what they are and why they occur.

When cutting for a show, your calories eventually get rather low. Simultaneously, to maximise satiety, you might increase how much NEAT you’re doing and train with high volumes to minimize muscle loss. In combination, this can lead to what is called low energy availability. Low energy availability is when your ratio of caloric intake to energy expenditure through physical activity is “low”.

Why is this relevant? Well, low energy availability has been linked to a variety of negative outcomes (mostly in females, but also in males) for both health and performance. Specifically, it seems to increase injury risk, reduce gains from training, decrease coordination, decrease concentration, make you more irritable, reduce muscle strength, etc.(1). It also likely results in immune suppression and a variety of other issues(1).

Taken from (1).

A reduction in coordination and concentration probably increases likelihood of form breakdown. Deviations in technique from what you’ve accustomed your connective tissues to likely increases injury risk. Thus, when in a state of low energy availability, the likelihood of injury probably goes up.

In addition, the reduction in available energy might reduce the recovery rate of connective tissues.

Anecdotally, being in a caloric deficit can reduce motivation to train. Evolutionarily speaking, this makes sense – your body likes to maintain its current bodyweight. When you’re eating fewer calories in an attempt to lose bodyweight, your body will try to reduce how much energy it’s expending (i.e. training and moving around) to reduce or cancel the caloric deficit you’re trying to establish. Thus, another challenge of preparing for a bodybuilding show is a reduction in your motivation to train. This specific challenge is large enough to warrant its own blog post.

This reduction in motivation can be especially deleterious to your progress since muscle mass retention is contingent on how well/much you train. Some evidence suggests that male bodybuilders are more susceptible to losing up to around 5KG of lean mass when dieting to get on stage, while females don’t seem to lose much(2). This difference may be due to differences in conditioning standards or it could be due to gender-specific physiological differences.

Note: take evolutionary reasoning with a grain of salt. It’s useful when trying to explain something to a layperson, but it probably shouldn’t be taken as particularly convincing evidence.

What can we do about an increase in injury risk?

The primary training-related problem during prep is probably an increased injury risk. Because deviations in technique from what your body is used likely contributes to injury risk, using machines can help reduce injury risk.

Another modification you can make during prep is to slow down the tempo of each repetition, assuming you weren’t already doing so. Slowing down the tempo probably reduces injury risk in at least two distinct ways. First, it reduces injury risk by reducing how much weight you can use. Doing 5-10 reps with a controlled tempo is harder than doing them with an explosive tempo, which will require you to use less weight. Secondly, because the bar speed is slower, the forces your connective tissue and muscles experience will be lower.

That being said, don’t slow down the tempo too much. We have evidence suggesting total repetition durations of more than about 8 seconds may be slightly worse for muscle growth than repetition durations between 0.5-8 seconds. In the same meta-analysis, there did seem to be a trend for faster tempos (i.e. 0.5-4 seconds vs 4-8 or 8+ seconds/rep) to be more hypertrophic. However, this could just be noise – the sample sizes of the individual studies weren’t particularly large and the meta-analysis only included 8 studies. To be on the safe side, I think limiting repetition tempos to about ~4 seconds maximum is a good choice(3).

Another thing we can do to offset the increased injury risk is to do more repetitions per set. Intensities of ~30-80%1RM grow you roughly equally on a set per set basis(4,5). With occlusion training, you may even be able to go as low as 20%1RM and still maximise muscle growth per set(6,7).

While we don’t really have any direct evidence to support an increased injury risk with heavier relative intensities (%1RM), there is a fairly large amount of corroborating anecdotes and/or indirect evidence. First, anecdotally, more people report getting injured when training with heavier weights – at least in my experience. Secondly, within the strength sports (i.e. bodybuilding/strongman/powerlifting, etc.), bodybuilding may have the lowest injury rates(8). While this can’t be directly attributed to lifting lighter weights for more reps, it is certainly plausible that it would contribute (alongside a greater exercise variety etc.). Indeed, lifting lighter weights means connective tissues experience lower peak forces.

A cool byproduct of shifting your training to more higher rep sets is that higher rep sets typically result in higher energy expenditure too(9). For fat loss, this is definitely a benefit since it means we can eat slightly more food, resulting in decreased hunger.

Another small training change that may be worth making to attenuate injury risk is placing the most technique-heavy exercises first in your sessions. Fatigue likely interferes with your ability to have good technique and bad technique probably contributes to increasing your injury risk.

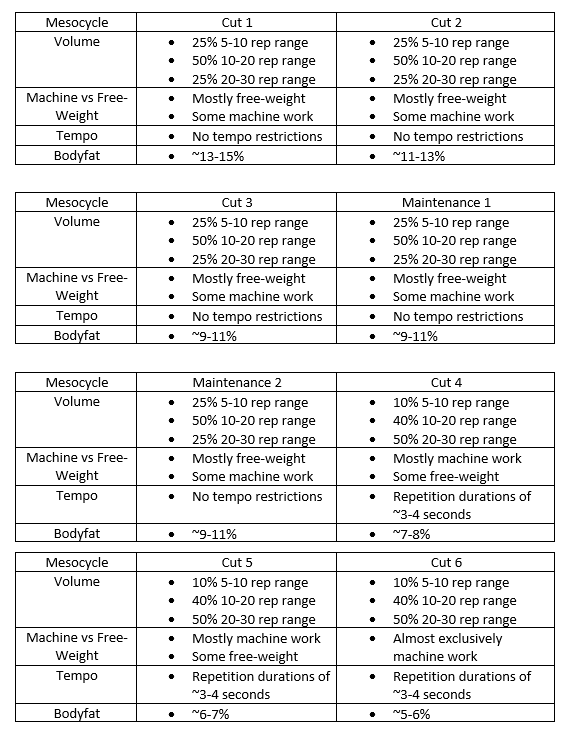

Bringing it all together; an example

1. Mountjoy, M. et al. The IOC consensus statement: Beyond the Female Athlete Triad-Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S). Br. J. Sports Med. 48, 491–497 (2014).

2. Roberts, B. M., Helms, E. R., Trexler, E. T. & Fitschen, P. J. Nutritional Recommendations for Physique Athletes. J. Hum. Kinet. 71, 79–108 (2020).

3. Schoenfeld, B. J., Ogborn, D. I. & Krieger, J. W. Effect of Repetition Duration During Resistance Training on Muscle Hypertrophy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sport. Med. 45, 577–585 (2015).

4. Schoenfeld, B. J., Grgic, J., Ogborn, D. & Krieger, J. W. Strength and Hypertrophy Adaptations Between Low- vs. High-Load Resistance Training. J. Strength Cond. Res. 31, 3508–3523 (2017).

5. Lasevicius, T. et al. Effects of different intensities of resistance training with equated volume load on muscle strength and hypertrophy. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 18, 772–780 (2018).

6. Boyle, S. H. et al. The Effects of Tryptophan Enhancement and Depletion on Plasma Catecholamine Levels in Healthy Individuals. Psychosom. Med. 81, 34–40 (2019).

7. Hughes, L., Paton, B., Rosenblatt, B., Gissane, C. & Patterson, S. D. Blood flow restriction training in clinical musculoskeletal rehabilitation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 51, 1003–1011 (2017).

8. Keogh, J. W. L. & Winwood, P. W. The Epidemiology of Injuries Across the Weight-Training Sports. Sport. Med. 47, 479–501 (2017).

9. Brunelli, D. T. et al. Acute low- compared to high-load resistance training to failure results in greater energy expenditure during exercise in healthy young men. PLoS One 14, 1–14 (2019).